Matthías Brugman (Puerto Rico) (1811-1868)

Matthias Brugman was the descendant of Dutch Jews, probably of Spanish origin, who migrated to Curaçao. His mother was from a Haitian creole family that had moved to Puerto Rico. Brugman was baptized at the St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans, but his family continued to practice Judaism in secret. A relative reported seeing Brugman's elderly sons secretly lighting Friday night candles in the early 20th century. When Brugman was five,his family relocated to Puerto Rico. In 1868 he was the owner of a farm in Las Marías, in Western Puerto Rico and one of the leaders of a plot to rise up and throw off Spanish colonialism. The revolt was timed to coincide with the Cuban Grito de Yara, but when word came that their plans had been betrayed, and a boat full of weapons seized in St. Thomas, the uprising was launched early, on September 23. Known as the Grito de Lares, the uprising was fairly quickly put down. Matthías Brugman continued to fight a guerrilla campaign from the mountains for several weeks, but was shot and killed whena servant betrayed his hideout to the soldiers. In the 1960s, my father, Richard Levins, used the pseudonym Manuel Brugman for some of hispolitical writings, in honor of Matthías.

Fabio Grobart (Cuba) (1905-1994)

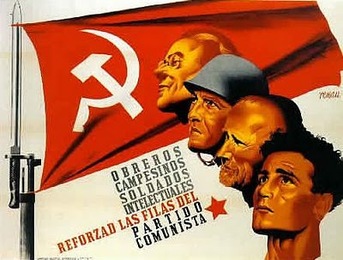

Fabio Grobart was born Abraham Sinjovich in Bialystok, Poland in 1905. He joined the Young Communist League of Poland in 1922, was placed under sentence of death and left Poland for Cuba in 1924. He was 19 years old, and worked as a tailor's assistant. The following year he became one of the founding members of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC). According to historian Moises Asis, three other Ashkenazi Jews also took part in the Party's founding, surnamed Grimberg, Vasserman, and Gurbich.

Abraham used a number of pseudonyms, including Fabio, the name by which he is known in Cuba. He was an active member of the PCC all his life, and played an important role in shaping the socialist path of the revolution. In 1965 he was part of the first Central Committee of the PCC. In 1973 he was named president of the Institute of the History of the Communist Movement and Socialist Revolution of Cuba. In 1976 he was elected to the National Assembly of Popular Power.

Abraham used a number of pseudonyms, including Fabio, the name by which he is known in Cuba. He was an active member of the PCC all his life, and played an important role in shaping the socialist path of the revolution. In 1965 he was part of the first Central Committee of the PCC. In 1973 he was named president of the Institute of the History of the Communist Movement and Socialist Revolution of Cuba. In 1976 he was elected to the National Assembly of Popular Power.

Cuban Communists in the Machado Years

Moisés Raigorodski Suría (Cuba) (1914-1936)

Moisés Raigorodsky was born to a poor family in the Ukrainian port city of Odessa in 1914. Five months after his birth Russia entered WWI and his father Germán was drafted. His mother Sonia took him to live with her parents. Soon after, German was reported killed, but four years later, he returned to Odessa, having spent the time in a concentration camp for prisoners of war. When Moisés was nine, his parents decided to emigrate to the United States, where German's brothers lived, and had sent for them. But their ship stopped in Havana, and they decided to try their luck there.

They established themselves in the Belén neighorhood of the city, and German opened a print shop. Moisés excelled in school, and adapted quickly, becoming fluent in Spanish, and was known as "El Rusito." At thirteen he passed the entrance exams for the Institute of Secondary Education and enrolled in high school where he studied music. It was 1927, and the Machado dictatorship had unleashed a reign of terror, outlawing labor unions, and using torture and assassination to suppress worker and student movements. Moisés' arrival Instituto coincided with an upsurge in student activism, which he joined. When he was fifteen, the Cuban communist leader Julio Antonio Mella was murdered in Mexico, and Moisés took part in the student mobilization that followed,during which a number of important student leaders were killed and wounded. This experience further radicalized Moisés.

They established themselves in the Belén neighorhood of the city, and German opened a print shop. Moisés excelled in school, and adapted quickly, becoming fluent in Spanish, and was known as "El Rusito." At thirteen he passed the entrance exams for the Institute of Secondary Education and enrolled in high school where he studied music. It was 1927, and the Machado dictatorship had unleashed a reign of terror, outlawing labor unions, and using torture and assassination to suppress worker and student movements. Moisés' arrival Instituto coincided with an upsurge in student activism, which he joined. When he was fifteen, the Cuban communist leader Julio Antonio Mella was murdered in Mexico, and Moisés took part in the student mobilization that followed,during which a number of important student leaders were killed and wounded. This experience further radicalized Moisés.

Student protests against Machado.

At the age of seventeen, he joined the Ala Izquierda Estudiantil, but continued his musical studies and began to write. In 1932, he published his first book, Albores Literarios and began writing theatre pieces in which he also acted, based at the Centro Hebreo de la Habana. There he founded the journal El Estudiante Hebreo, in Yiddish and Spanish, in which his writing also appeared. The journal then became the official organ of Juventud Comunista Hebrea, and a focus of activism against the dictatorship. This brought down repression on the Círculo de Estudiantes Hebreos, and his father's press was closed. He continued to be active in radical Jewish organizations, including the Sociedad Unión Cultural Hebrea. At nineteen, Moisés was a veteran organizer. He was chosen to direct the work of the Liga Juvenil Antiimperialista at the Instituto de Segunda Enzeñanza in Havana, where he did intensive organizing, and that year he joined the youth branch of the Cuban Communist Party, the Liga Juvenil Comunista, as part of Cell #5 in the barrio of Belén. He was very active in the mobilizations that led to the general strike of March, 1933 which brought down the Machado dictatorship.

Parque Central, La Habana

During the progressive Grau government, Moisés was very active in the creation of agricultural cooperatives and soviets in the Cuban countryside, and joined the popular "Peace and Justice" militias. In the fall of 1933, the ashes of Julio Mella were brought back to Cuba and a vigil where they were to be honored was attacked by the police, with the backing of the army, leading to a stampede and massacres. Moisés distinguished himself by disarming several policemen who had trapped some of his comrades in a dead end street. This period saw repeated attempted coups by the military against the Grau regime, and Moisés was active in its defense. He was chosen to take the Communist Party message to a number of sugar mills, calling for worker control of the mills. While speaking at the Senado sugar mill, the rally was ambushed, and another massacre took place, with twelve dead, most of them bleeding to death while trying to hide in the cane fields, while seventy more seventy were seriously injured. Raigorodsky defended himself with a pistol, was wounded in the shoulder, and was able to hide in a truck full of merchandise and make it back to Havana.

Castillo del Príncipe

At the time of the 1934 military coup, headed by Fulgencio Batista, which brought down the Grau government, and put President Mendieta in power, Raigorodsky was considered a dangerous radical, well known to the repressive forces, and within a month he had been arrested and sent to the much feared Castillo del Príncipe. There he was separated from his comrades and placed in the criminal population, doing hard labor, but he used the opportunity to organize among them. Mass mobilizations in his favor eventually secured his release, but the political police had him under surveillance.

María Luisa Lafita, Pedro Vizcaino and family.

Things were going badly for the revolutionary movement, and the government took action to crush the student movement. In May of 1934, the army occupied the Escuela de Artes y Oficios. The students responded by barricading themselves in the Instituto de la Habana. The standoff was resolved, but a few weeks later, during a right wing rally in the Parque Central Raigorodsky climbed up the statue of José Martí, and put a bandage over his eyes, saying he didn't want the father of the country to see such insults. This was the last straw for the Medieta government, and the decision was made to assassinate Moisés under the pretext that he was an agent of Moscow. In spite of the danger, Moisés took part in a violent confrontation with right wing "Green Shirts," leading a group of Juventud Comunista activists. He was identified as being among the attackers and his family was placed under house arrest. It was decided that he should go into hiding, and he was hidden in the house of communist Maria Luisa Lafita, along with several other young militants.

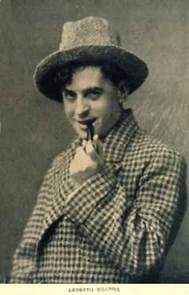

Actor Ernesto Vilches.

In August, 1933, the Party was able to smuggle him first to Mexico and then into exile in Spain. He was 22 years old. He spoke four languages, was a fine violinist and dramatist. He knew no one except his Communist Party contacts, and life was difficult. He peddled books, and thanks to his linguistic skills, managed to get some translation work with progressive publishers, but he knew very few people and was quite isolated. In April of 1935, Maria Luisa Lafita and her husband Pedro Vizcaíno arrived in Madrid, having also been forced to flee Cuba. Through a Spanish radical who had spent time in Cuba, he and his friends were introduced to a circle of Cuban exiles based at La Cubana boarding house. Together they founded the Asociación Antiimperialista de Revolucionarios Cubanos. Raigorodsky had affiliated with the Spanish Communist Party, and continued his political activism, but was struggling to survive economically. Then he followed up an a contact with Spanish actor Ernesto Vilches, whom he had met in Cuba and got a part in Vilches' film "El Preso 113." This role paid well and he was able to use his salary to help support his fiends at the boarding house, all of whom were struggling financially.

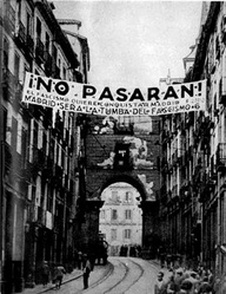

By this time fascism was on the rise and in early 1936 Raigorodsky joined the Milicias Antifacistas Obrero-Campesinas, in preparation for the expected fascist takeover. When the military uprising came in July, 1936, Raigorodsky, along with many of his Cuban comrades, was among the first to arrive at the Cuartel de la Montaña to try to block the troops from leaving. At the end of July, he and the other Cuban exiles became founding members of the famous Quinto Regimiento, the combat unit formed by the Communist Party to stop the fascist advance. At the same time he was one of the founders of the Sindicato de Artistas y Escritores, which planned to bring cultural activities to the front. He was immediately named a political commissar and military commander.

After forty days in combat, he became seriously ill and as evacuated to a hospital where many Cubans and other foreigners, including the photographer Tina Modotti, worked tending the wounded. There he spoke of his intention, should he survive, of writing a book about the solidarity work in these hospitals. In October he visited Madrid again, with his sweetheart, a young drama student with whom he was very much in love and intended to marry after the war. Madrid was then under siege by the fascists. Raigorodsky returned to the defense of the city during on of the worst moments of the war. The fascists had announced the Madrid would fall to them on November 7th, but the people of Madrid learned the details of the enemy plans and defended the city ferociously under the slogan "No pasarán." Sometime between November 6 and 8,1936, Moisés Raigorodsky was killed by a grenade while fighting to defend the city. Madrid successfully resisted for two and half years more, until the end of the Spanish Civil War. Moisés Raigorodsky, "El Rusito" never fulfilled his dream of returning to Cuba to take part in the revolutionary movement against Batista's forces, but his name is honored as a hero of that movement.

Irene Esser de Delano ( Puerto Rico ) (1919-1982)

Self-portrait, with husband Jack Delano in background.

Self-portrait, with husband Jack Delano in background.

Irene Esser was born in the United States and raised in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Her father was one of the first Jewish doctors licensed to practice medicine there. Her mother was from Odessa, Ukraine. She studied art in Philadelphia, where she met and married Jack Delano. In 1946, the couple moved to Puerto Rico, where they worked together as artists, and making educational films. Irene introduced silkscreen to a generation of influential Puerto Rican graphic artists, including Lorenzo Homar and Rafael Trufiño. Homar, in turn, taught it to Cuban artists, shortly after the triumph of the Revolution, thereby shaping the future of the highly influential Cuban poster art movement. (to be continued.)

Jack Delano (Puerto Rico) (1914-1997)

Jack Delano was born Jacob Ovcharov in the village of Voroshilovka village, in the Guberniya of Podolia, near Vinnytsia, Ukraine. His mother Sonia was a schoolteacher. His father was an officer in the Red Army. In 1923, his family migrated to the United States, settling in Philadelphia. (to be continued.)

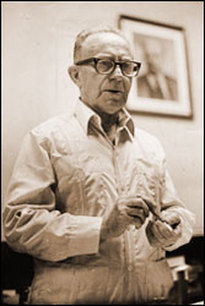

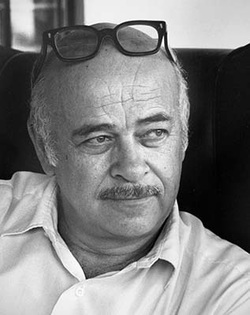

Richard Levins (1930-2016 )

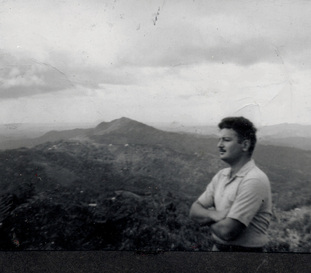

In Maricao, early 1950s.

Richard Levins was an internationally recognized mathematical biologist and ecologist. He was born in Brooklyn, New York into a Ukrainian Jewish family. His father, Reuben Levins, was a leader of the Young Communist League and a radical lawyer, and his grandmother Leah Shevelev, who raised him, was a feminist and labor organizer who also worked with Margaret Sanger educating immigrant women about birth control.

Levins joined the Communist Party in his teens. In 1948 he met Rosario Morales, a young Puerto Rican communist. They married in 1950 and when Levins was blacklisted, and faced a possible military draft to fight in the Korean War, the couple moved to Puerto Rico. There they became close friends with Alabama communist Jane Speed and her husband, communist labor leader and journalist Cesar Andreu Iglesias. While staying with Rosario's aunt looking for work, Levins found out from a nationalist neighbor that the FBI was visiting each place where he applied, telling employers not to hire him.

On the advice of Jane Speed, the couple bought a farm in Maricao and sold vegetables and eggs. From 1956 to 1960 Levins attended Columbia University in New York City, and in 1959 was subpeonaed by the House Unamerican Activities Committee and questioned about his activities in the Puerto Rican left. He refused to testify and walked out of the hearings.

Levins joined the Communist Party in his teens. In 1948 he met Rosario Morales, a young Puerto Rican communist. They married in 1950 and when Levins was blacklisted, and faced a possible military draft to fight in the Korean War, the couple moved to Puerto Rico. There they became close friends with Alabama communist Jane Speed and her husband, communist labor leader and journalist Cesar Andreu Iglesias. While staying with Rosario's aunt looking for work, Levins found out from a nationalist neighbor that the FBI was visiting each place where he applied, telling employers not to hire him.

On the advice of Jane Speed, the couple bought a farm in Maricao and sold vegetables and eggs. From 1956 to 1960 Levins attended Columbia University in New York City, and in 1959 was subpeonaed by the House Unamerican Activities Committee and questioned about his activities in the Puerto Rican left. He refused to testify and walked out of the hearings.

Pro-Cuba march, Puerto Rico, 1960.

Levins was an early member of the Movimiento Pro Independencia, founded in 1959, just after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution. In 1961 he was hired to teach biology at the University of Puerto Rico, where he worked closely with the student group, Federacion Universitaria Pro Independencia. In 1964 he was invited to Cuba to help redesign the Departent of Biology at the Universidad de la Habana, beginning a lifelong collaboration with Cuban scientists. In 1965 he participated in a Universidad de Puerto Rico strike and teach-in against the Viet Nam War. When speakers were refused access to the campus they leaned a ladder against the outside of the campus fence and spoke to students gathered inside. The left journal La Escalera, named for the incident, was founded that year, and he served as a writer and member of the editorial board. His influential 1965 essay "De rebelde a revolucionario" continues to inspire new generations of Puerto Rican radicals. He was active in the fight to expel the U.S. Navy from the islands of Culebra and Vieques, which was used for military exercises.

In Hanoi, December, 1970.

In 1967 he was denied tenure at the Universidad de Puerto Rico because of his political activism, and left Puerto Rico, accepting a job at the University of Chicago. In 1968 he taught at the Universidad de la Habana for the summer. In 1970 he traveled to Hanoi as part of the delegation of radical scientists, and on his return, founded Science for Viet Nam, an offshoot of Science for the People, to which he also belonged.

In 1975 he began teaching at the Harvard School of Public Health, where he directed the Human Ecology Program. He continued to work with Cuban scientists, training a generation of ecologists, collaborated on many research projects and helped develop sustainable farming practices. In 2002 he received an honorary doctorate from the Universidad de la Habana, and in 2004 was inducted into the Cuban Academy of Science. He wrote extensively about Cuba, Marxism, ecology, science under capitalism, mathematical modelling, and complexity, and through his alter ego, Isidore Nabi, wrote political satire. He was the co-author, with Richard Lewontin, of The Dialectical Biologist and Biology Under the Influence. He died inCambridge, MA in January, 2016

In 1975 he began teaching at the Harvard School of Public Health, where he directed the Human Ecology Program. He continued to work with Cuban scientists, training a generation of ecologists, collaborated on many research projects and helped develop sustainable farming practices. In 2002 he received an honorary doctorate from the Universidad de la Habana, and in 2004 was inducted into the Cuban Academy of Science. He wrote extensively about Cuba, Marxism, ecology, science under capitalism, mathematical modelling, and complexity, and through his alter ego, Isidore Nabi, wrote political satire. He was the co-author, with Richard Lewontin, of The Dialectical Biologist and Biology Under the Influence. He died inCambridge, MA in January, 2016

Judith Berkan (Puerto Rico)